I haven't been active on my blog lately and to compensate for that I am posting an image featuring mostly my recent pots.

Saturday, June 22, 2024

Wednesday, January 31, 2024

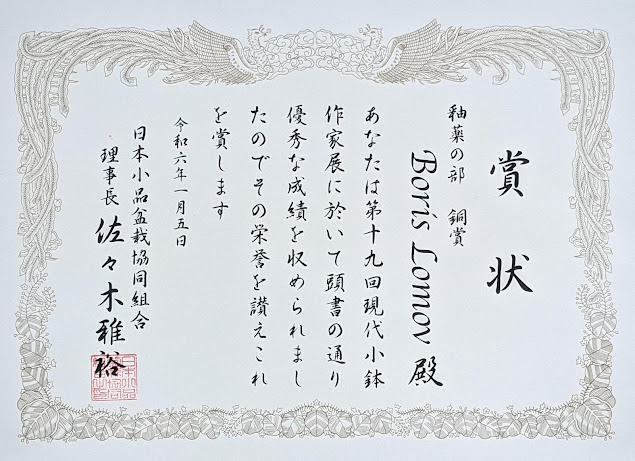

Success at 19th Contemporary Small Bonsai Pot Artists Exhibition held in conjunction with 49th Gafu Exhibition, January 2024, Kyoto, Japan

I truly abandoned my blog… Too much typing hurts my hands these days. I feel like I can get away with writing anything here because no one reads it! Anyway, I am writing suddenly because I won a bronze award in glazed pot category at Gafu-ten this year! The pot in question is the result of hundreds of less successful attempts made after more than ten years of my participation in dozens of wood-kiln firings. The pot was made at Macquarie Hill Potters studio and fired in the Ceramic Study Group wood kiln between two COVID lockdowns in 2020. As a hobby potter, I am especially proud of this achievement because I competed against the best Japanese professional craftsmen. Anyway, below are the photos.

Tuesday, August 27, 2019

Bonsai demonstration by Juan Llaga from Philippines

Last weekend I attended a demonstration by a Pilipino

bonsai artist Juan Llaga at the Tops Weekend organised by the Illawarra Bonsai

Society. As always, I really enjoyed the event, but was mildly disappointed by

this year’s international demonstrator.

Images above show ‘before and after’ of the

first part of his demonstration. I honestly couldn’t see the point of it. He

could have used a miniature umbrella instead of a tree to achieve the same effect.

Images below show ‘before and after’ of the second

and main part of his demonstration. The forest planting assembled by Juan lacks

cohesion and falls short in the following areas:

- sub-optimal arrangement of trees in terms of their height;

- inconsistent angles at which the trees are planted;

- thoughtless

branch arrangement;

- unnecessary and repetitive jins.

In the week following the demonstration, I came across something written by Ming dynasty scholar Shih T'ao. He wrote about painting trees: "The ancients were in the habit of representing trees in groups of three, five, nine or ten. They painted them in their various aspects, each according to its distinctive appearance; they blended the uneven heights of their silhouettes into a living, harmonious whole. I like painting pines, cedars, old acacias and junipers, often in groups of three of five. Like heroes performing a war dance, they display a wide variety of attitudes and gestures; some lower their heads, others raise them; some double up on themselves, others point straight and boldly upward." This passage reminded about the weaknesses in Juan Llaga's forest planting composition.

Sunday, June 09, 2019

Demonstration by Masayuki Fujikawa at Bonsai by the Harbour, Sydney

Yesterday,

I attended a bonsai demonstration by Masayuki Fujikawa. He is a second generation owner of Fujikawa Hosei-en nursery in Nasushiobara. Mr. Fujikawa was a Masahiko Kimura’s apprentice for eleven years and has been an independent

bonsai artist for the past ten years. He won the professional bonsai competition

Saikufu-ten twice.

During

the demonstration Mr. Fujikawa came across as friendly, knowledgeable, sharing

and delivered an inspiring demonstration. He did a demonstration on an oddly

shaped Japanese Black Pine which had most of its branches on one side. The end

result was convincing considering the limited time and the quality of the material (see before and after images above). He was interpreted

by Adam Webster who is an Australian apprentice at the Yuuki-En Bonsai Nursery

near Tokyo. Adam is a really nice guy and has done a great job as the

interpreter.

My visit to Ha Long Bay

Bonsai often draws inspiration from traditional Chinese paintings, and many

famous paintings of the Ming and Qing era are inspired by the weathered hills

of Guilin in South China. These hills are karst or eroded limestone formations.

I’ve never seen Guilin, but during my trip to Vietnam I got to see spectacular karst

formations of Ha Long Bay. I felt that potted trees and miniature landscapes, omnipresent

in Vietnam, draw a lot of inspiration from the natural wonder of Ha Long Bay.

A modern-day bonsai kōan

A Japanese friend once told me a modern-day bonsai kōan. Kōan

is the Japanese word for a paradoxical

anecdote or a riddle used by Zen masters to make their disciples understand something.

So, here it is.

Once upon

a time, during Japan’s economic boom, there was a corporation. Back in those

days, companies supported employees’ recreational activities and this

particular one sponsored an in-house bonsai club. The company hired a bonsai

master to instruct the club members and his bonsai were displayed in the headquarters

foyer. Every day, hundreds of people passed by the bonsai display, but hardly

anyone took notice of it.

All good

things come to an end and with the onset of economic depression the company

began to cut costs. It gave the boot to the bonsai master, but asked the club

to continue displaying bonsai in the foyer. The employees happily started

showcasing their own work and suddenly everyone began noticing and talking

about the bonsai in the foyer.

Why do

you think trees created by the bonsai master were not obvious, while bonsai

trees by amateurs were conspicuous?

Wednesday, August 15, 2018

Bonsai containers in Vietnam

In Vietnam potted plants are omnipresent and during my brief visit in

2016 I scrutinised every flower pot in my way. The

containers were made of concrete, ceramic and stone. It seems that concrete pots were most

common. They are used for larger trees and miniature landscapes. Some were

painted with bright colours and looked rather tawdry. The examples shown in the

images below are somewhat more sophisticated.

Needless to say, there were lots of ceramic pots.

Most of them looked tacky. Images below show examples which looked particularly

native.

There was one type of ceramic containers that I really

liked. Initially, I saw them in a couple of antique shops in Hanoi and then I

came across of a small collection in a private bonsai garden in Hoi An where I

took the photos shown below. I am not sure if these containers were locally

produced or imported. They could be either antique or vintage. I am not sure of

their age because the deterioration of the glaze can be attributed to the low

temperature firing used in their production. If these pots are earthenware than

it’s just a matter of few decades for the glazes to start peeling off. The

actual decoration on these pots is very crude, but the glaze deterioration

gives them this aged look and the ephemeral rustic quality akin to wabi-sabi.

Finally, I saw a small number of containers carved out of stone and when

I looked though my photos found only one shown below.

Sunday, April 01, 2018

Bonsai pot stragglers from last year

A couple of medium size pots I made in

2017, which took a long time to fire in an electric kiln. The one on the left

is rectangular with rounded corners and the one on the right is oval. Both are

tests for one glaze over another.

Saturday, January 20, 2018

Wood-fired bonsai pots made in 2017

2017 was uneventful for me in terms of bonsai or bonsai pot making. I

made only ten bonsai pots last year, but those that are wood-fired are worth

showing off. Below is probably the best pot I made last year. Decorated with

rutile glaze.

Below is a pot with a Chinese cheng-yu proverb inscribed with underglaze.

The one below is decorated with a blue glaze that got altered by natural ash.

Below is an unglazed pot with natural ash formed on one side.

Last but not least, another unglazed pot made in Namban style.

Friday, January 19, 2018

The Temple of Literature, Hanoi

The Temple of Literature is basically what is left of the Imperial

Academy created to educate Vietnam’s elite in medieval times. This is where they

held Vietnam’s civil service examinations and I can’t help thinking that it

mirrored Chinese imperial

examination system. This educational institution was dedicated

to Confucius and a couple of sages and scholars and functioned from 1076 till 1779.

I would say it had a pretty good run.

When I started writing this post it was difficult for me to figure out which

photos have been taken in which part of the temple, so I ended up drawing a plan

shown below to make the post more visual and somewhat structured.

Images below show the main gate of the temple. I am not an expert on traditional

Vietnamese architecture, but it felt like there is something distinctly

Vietnamese about it.

Since the temple is surrounded by walls and its courtyards are separated

from each-other by walls as well, there are quite a few gates. They are all

different and well-integrated with the surrounding gardens. The image below

left shows the Dai Tai gate. It is one of the side gates located in the first

courtyard. The image below centre shows a bit of the first courtyard and the

gate leading to the second courtyard. Another gate is shown in the image below

right. It is called the Khue Van pavilion and it provides a passage from the Second

to the Third Courtyard.

The temple gardens feature a number of ponds. Images below show two

examples. The image on the left shows one of the ponds in the First Courtyard

and the image on the right shows the Thien Quang well in the Third Courtyard.

Below are images of the Fourth Courtyard

featuring trees growing in large concrete planters.

The focal point of the whole complex is the main hall of the temple

located in the Fifth Courtyard. Below are images showing some of its features.

The rightmost image shows the altar to Confucius.

Finally, let’s make this post relevant to the topic of bonsai. Below are

some examples of potted trees photographed in various areas of the temple.

Images below show larger potted trees located in the Fourth

Courtyard.

What can I say about the potted trees in the temple? They all display

some degree of styling. None of them are terribly refined, but given the

context, they probably don’t have to be. To me they provide historical context

for bonsai by linking Oriental style potted plants with penjing.

Saturday, July 08, 2017

The Temple of the Jade Mountain, Hanoi

Last year, I visited the Temple of the Jade Mountain located on Jade

Island near the northern shore of the Lake of the Returned Sword (Ho

Hoan Kiem) in Hanoi. Image below shows the island with the temple lit up at night.

The lake has this epic name that come from a legend. I am not going to repeat

Wikipedia here, but it’s basically a Vietnamese version of the Excalibur story

and the bottom line is “If you have been given a magic sword, one day you need

to give it back”. Just like in real life good things don’t last and that is

what makes them “magic”. In the legend, the sword is returned to the Golden

Turtle God which is shown in the image below left. The belief in this deity was

inspired by the presence of a large species of soft-shell turtle (Rafetus swinhoei) in the lake. It is believed

to be locally extinct and the last known individual was found dead just four

months before my visit.

The

temple dates back to the 18th century and is dedicated to several historical

figures. Among them a couple of scholars, but my favorite is general Tran Hung

Dao who repelled three Mongol invasions during Kublai Khan’s rule in the

13th-century.

The

temple has several architectural landmarks. The image below left shows the gate

with a large ink-slab placed on top of it (Dai

Nghien). The center image shows the Welcoming Morning Sunlight Bridge (Cau

The Huc) connecting Jade Island with the mainland. The image below right

shows the Moon Contemplation Pavilion (Dac Nguyet).

I

understand that it’s a Taoist and Confucian temple. The main temple

building shown in the images below was antique and quaint as opposed to freshly

painted buildings in the images above.

Some of the temple furniture was impressive. The door panels were

beautifully carved (images below). Statues of the temple deities looked

interesting too. There was also something different about the main incense

burner, probably the handles featuring horned qilin heads and the feet

featuring lion heads (centre image below).

My visit to Vietnam had nothing to do with my interest in bonsai, but

bonsai was there for me to find it. Buildings, hedges and parapets in the

temple grounds form many secluded areas decorated with many cay canh trees. Typically, they were large

size, styled trees grown in decorated concrete containers.

Examples of such courtyards with cay

canh trees are shown in the images above and below.

The temple’s three most impressive cay

canh trees are shown in the images below.

They are located on a platform housing the

Pavilion Against Waves (Dinh Tran Ba). This pavilion can be seen in the

very first set of images of this post. Below are more images showing the

platform with the trees arranged on it.

Other cay canh trees in the

temple were not as refined and images below show some examples.

Finally, one cannot talk about the Temple of the Jade Mountain and the Lake of the Returned Sword without mentioning the

Turtle Tower (Thap Rua) located in

the middle of the lake. Images below show this scenic landmark.

Saturday, June 10, 2017

Origins of Nanban pottery: Hội An, Vietnam

I was aware of Namban pottery for a long time, but since my trip to

Japan in 2015 this interest became deeper. This fascination arose from the fact that Namban’s

origins are shrouded in mystery and I am a person who likes to get to the

bottom of things. The best explanation of Namban origins I found so far is here

http://lomov.blogspot.com.au/2015/09/namban-bonsai-pots.html.

South-East Asia has always been a suspect provenance of Namban pottery

and last year, I made a Namban discovery of my own, while traveling in

Vietnam. During a visit to the Museum of Folk Culture in Hội An, I came across

of a ceramic piece that simply “screamed” Namban at me (see image below left). For

comparison, the image below right is a contemporary piece of similar shape and

size made by a renowned Japanese potter Yukizyou Nakano also known as “Gyozan”.

I learned at the museum that the pot has been made in the Thanh Hà

village near Hội An. Potters of Thanh Hà village have been making functional low-fired

unglazed pottery since the beginning of the 17th

century. Nguyen Dynasty records of the time tell us that their wares have

been transported by river to the nearby commercial port of Hoi An and from

there exported to the coastal provinces of Central Vietnam and abroad. All this

got me thinking and I realised that six historical occurrences took place at

the same time, all of them at the beginning of the 17th century. Here they are:

1. Potters settle in Thanh Hà village near Hội An in Vietnam.

2. Hội An becomes the most important trade port in the East Vietnam Sea.

3. Tokugawa Ieyasu issues permits to Japanese merchants to trade with Vietnam.

4. A thriving Japanese trading settlement springs up in Hội An.

5. Increasing demand for rustic and unassuming ceramics for tea ceremony in Japan.

6. Earliest Namban pottery appears in Japan.

When the facts line up like that, Vietnamese provenance of some of the early

Namban ceramics becomes quite plausible. I could also add here that the oldest extant Vietnamese ceramics have been found in Japan, in a tomb at Dazaifu and they date back to 1330. Vietnamese ceramics made in the 15th and 16th centuries also have been found in Okinawa, Nagasaki, Hakata, Osaka, Sakai and Hiroshima.

One architectural remainder of the former Japanese presence in Hội An is

the Japanese Bridge. At the beginning of the 17th century Japanese merchants in

Hội An were influential enough to build this bridge across the river to trade

with the local residents (see the images below).

Saturday, March 25, 2017

Bonsai pot leftovers from last year

Images above show a couple of unglazed electric kiln fired pots I made last year. The one on

the left is inspired by rectangular nanban pots, which are less common than the

round ones. It was also the first time I tried a combination of slab and coil

building to form a bonsai pot (dimensions 20 x 27 x 11 cm). This technique is

used by some Japanese potters to make large bonsai pots. The pot on the right

was my attempt to imitate this slip decoration technique that I’ve seen on some

Chinese pots. This pot is small, about 10 cm in diameter.

My Fergus Stewart pot

This year’s AusBonsai Market held at Auburn Japanese Garden was great.

My deep gratitude to the organizers. I was just curious about what’s new and one

stall selling bonsai pots immediately got my attention. The first thoughts that

came to my mind were wood-fired ceramics by a highly skilled potter, but not a

career bonsai pot maker. All pots were on the larger side, round, skilfully

thrown on a potter’s wheel. Some of them were about a meter in diameter! You

have to be a potter to appreciate that. I had to know who the potter is and the

stall owner was too happy to tell the story. A Scottish ceramic artist Fergus

Stewart with a passion for wood-fired ceramics worked in Australia between 1981

and 2002. Around 1999 while working at the Strathnairn Ceramics Workshop in

Canberra, Fergus Stewart was commissioned by a Canberra bonsai grower John

Remmel to make a series of bonsai pots. The examples of pot shapes and glazes given

by Remmel were illustrations from “Matsudaira

Mame Bonsai Collection Album” published in 1975. Stewart had to develop

several glazes to match the illustrations in the album. Most pots had either a

chop mark “FS” or signed “Stewart”. It turns out that the lot of them was never

used and ended up for sale in this year’s bonsai market. Many of the pots had

no feet and looked more like your typical English handmade functional stoneware

rather than bonsai containers. Perhaps this was the reason why this stall was

largely ignored by the market crowd. It’s a shame because they are a product of

great craftsmanship and would work with certain trees. Nevertheless, in some instances

Stewart did manage to capture the essence of a bonsai pot and I simply could

not resist buying one of those (see image below, round 6 x 40 cm).

Monday, March 20, 2017

Byōdō-in temple, Uji

During my short residency at Fujukawa Kuoka-en in Osaka a couple of

years ago, I was wandering what to do on my weekly day off. My bonsai

instructor Maeoka-san pointed at the obverse of a ten-yen coin and said: “Go to

Uji, it’s very peaceful there”. I

thought if this place is depicted on their money, it has to be amazing. I was

aware that Uji is famous for its tea, but knew little about Byōdō-in temple depicted on the coin. A

quick Internet search informed me that the temple began its existence in 1052

when a Fujiwara clan country house was converted into a temple. The

construction of its most beautiful and famous building known today as the

Phoenix Hall was completed in the following year (see images above and below).

The coolest thing about the Phoenix Hall is that it’s a wooden structure which

hasn’t been burned or destroyed for nearly a thousand years. What we see today

is roughly how it looked during the heyday of Heian period. So, for me,

visiting Byōdō-in was like time travel.

Byōdō-in museum was fascinating too, but photography was prohibited. All

temple buildings except Phoenix Hall were burnt down during a war in the 14th

century, so the other buildings reflect later architectural styles (see images

below). To sum up, Byōdō-in is one of the most beautiful places I’ve seen in

Japan.

Saturday, October 08, 2016

Daitoku-ji temple complex: Kōrin-in

Kōrin-in is one of those temples that are closed to visitors most of

the time. Fortunately, my visit to Daitoku-ji coincided with the time when its

doors were open to public. The temple is impressive, but there is not a lot of

information about it at ones fingertips. Luckily, Gregory Levine’s book titled

“Daitokuji: The Visual Cultures of a Zen Monastery” shed some light on the

temple’s history. Kōrin-in had begun its existence around 1520 as a family mortuary

for the daimyo of Noto Prefecture.

Its founding abbot Shōkei Jōfu was one of Daitoku-ji’s most venerated

monks. Following his death in 1536, Kōrin-in begun to function as his

mausoleum. At the end of the 16th century the temple transitioned to a mortuary

site for the Maeda clan and by the beginning of the 17th century became a

regular urban temple. During the Meiji period (1868-1912) it even functioned as

a hospital before being marketed as Ryōshō-ji. The original Ryōshō-ji site was destroyed,

but Daitoku-ji leadership needed to maintain the Ryōshō-ji brand and Kōrin-in

was a conveniently available surrogate for it. Once the new Ryōshō-ji was

reconstructed in 1932, Kōrin-in was reverted to being Kōrin-in again.

It wasn’t the only swindle in Kōrin-in’s history. I should mention that

the temple remained Shōkei Jōfu’s mausoleum throughout its existance. However,

in 1998 it’s been discovered that one of Kōrin-in’s main relics, a statue

venerated as the depiction of the temple’s founder Shōkei Jōfu was originally a

portrait of Ten’yū Jōkō, the founding abbot of now extinct Baigan-an temple.

This is especially baffling because Ten’yū was a prominent figure affiliated

with Daitoku-ji’s Northern faction (Daisen-in temple), while Kōrin-in’s founder

Jōfu belonged to the Southern faction (Ryōgen-in temple). Here goes my idea of

Daitoku-ji as one big happy family. The displacement of this statue probably

happened during the first years of Meiji period (following 1868) when things

got out of control due to the movement to abolish Buddhism and make Shintō the

state religion. Korin-in’s Abbot’s Quarters building or hōjō has been constructed between 1533 and 1552 making it one of

oldest extant buildings of its kind. The building is executed in Muromachi style

and goes well with Daitoku-ji’s overall character. Sliding door panels divide

its interior into eight rooms floored with tatami (see images above). The

building served various ritual, social and residential functions. The alter

room (butsuma) with the adjacent

chapel (shit-shū) situated at the

core of the building weren't open for viewing. Apparently, the alter room is

dominated by the portrait of Shōkei Jōfu and the “Jōfu/Ten’yū” statue mentioned

above. By the way, the leftmost image above shows the oldest extant example of tokonoma

alcove in Japan.

Temple gardens are always my primary interest, but I haven't been able to find any substantial information

about Kōrin-in’s gardens. Apparently, the dry garden along

the southern side of hōjō (images above) represents the idea of paradise according to Chinese mythology with its

rocks and azaleas symbolising mountains. One of the trees in this

garden is said to represent the “Baidara”

tree whose leaves were used for writing Buddhist scripture in ancient India. Those

Indian manuscripts were actually made of palm leaves and the Japanese word “Baidara” may have originated from the

Sanskrit word “patra” which means

writing sheets made of palm leaf.

Hōjō’s eastern side overlooks a moss garden (images above). I found no

information about its symbology. Its design features a wavy strip of bare

ground. I would like to know what it represents. May be a river?

Northern side of hōjō faces Kankyo-tei teahouse surrounded by a tea

garden (see images above). Apparently, Kankyo-tei’s name comes from a poem by tea

master Furuta Oribe (1544-1615) and it roughly translates as “solitude tea hut”.

Its design is a copy of famous Hassō-an teahouse designed by tea master Kobori

Enshū (1579-1647).

Above is a composite image of Kankyo-tei’s interior. Hassō-an and Kankyo-tei

follow a design called hassōnoseki or

"eight-windowed [room]". This design is attributed to Furuta Oribe who

was Enshū's teacher. The innovation of this design was more windows at varying

heights (see the image above), especially around temae-za (the place of the host). This created a “spotlight” effect

on the host performing the ceremony, which could be perceived as vane. On the

other hand, it made the ceremony more fun to watch, which could be perceived as

being attentive to guests. Tea master Sen Rikyū (1522-1591) liked it dark and austere

in line with the aesthetic principles of Zen, while Oribe liked it to be less

severe and more fun. I can see the merits in both views.

Images above show a little more of Kōrin-in. The leftmost image shows a

small shrine at the North-east corner of hōjō.

Center image shows a walkway leading from one of the temple’s buildings to hōjō. Rightmost image shows a courtyard

garden with stepping stones. Images below show little things here and there that

caught my eye.

I am really glad Kōrin-in was open on that summer day, last year.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)